|

| My parents in my father's office, after his release |

This post is about ADM Jabalpur Vs Shivkant Sukla (the Habeas Corpus case).

It is second post of the series 'It Lies In The Heart'.

For the first one see here.

It is second post of the series 'It Lies In The Heart'.

For the first one see here.

ADM Jabalpur Vs Shiv Kant Shukla AIR 1976 SC 1207: (1976)2 SCC 521: 1976 UJ (SC) 610: 1976 CrLR (SC) 303: 1976 CrLJ 1945 (SC) (the Habeas Corpus case) was decided on 28th April, 1976 and dealt with this question.

The High Courts had held in favour of maintainability but the Supreme Court overruled the unanimous view of the High Courts. The Supreme Court held that because of suspension of article 21, the habeas corpus petitions were not maintainable and the prisoners as well as the détenus lost their locus standi to challenge their illegal detention.

Fortunately, the view taken by the Supreme Court has been superseded by the Constitutional (44th Amendment) Act and now Article 20 and 21 cannot be suspended. In WP-C 494 of 2012 KS Puttaswamy Vs Union of India (the Puttaswamy case) {AIR 2017 SC 4161 = 2017 (10) SCC 1} the basic question referred to the nine judge bench was whether the right to privacy was constitutionally protected right and if the MP Sharma case (1954 SCR 1077 = AIR 1954 SC 300) and the Kharak Singh {1964 (1) SCR 332 = AIR 1963 SC 1295} were correctly decided. The court partly overruled these cases and held that the right to privacy is protected as part of Article 21 and the freedoms guaranteed by Part III of the Constitution. While doing so, they also specifically overruled the Habeas Corpus case. However, the discussion about the Habeas Corpus case is not redundant: its good to know that the judges are also ordinary mortals and how they react in difficult times.

This article was written 20 years after the Habeas-Corpus case was decided. It talks about the lawyers and judges connected with that case and what has happened to them. Since then, it has been updated.

It was a matter of speculation as to why Nani Palkhivala, the greatest lawyer of that time, did not appear in the Habeas Corpus case. I consider myself privileged that we (Palkhivala and myself) were pen friends. We used to exchange letters on varied topics. I had written a letter to him inquiring about his non-appearance in the case. I did not publish his letter earlier for the reason that LM Singhvi chose not to publish it. This reason is mentioned in the succeeding paragraphs.

When I had just become a judge, LM Singhvi delivered a talk at the Allahabad museum. He was knowledgeable as well as good orator. I went there to listen to his talk.

After the talk, LM Singhvi came to know that I was also there. He came over to me and said that he was the chief editor of the book about 'Selected writings of Palkhivala' and had all letters written by Palkhivala to me; Palkhivala was keen that one of the letters written by him to me, about his non-appearance in the Habeas Corpus case should be published in the book but he was not including the letter for the strong language used in the letter. This was also the reason that I had not published the letter earlier. But since then, a book has come into existence mentioning a different reason for non-appearance of Palkhivala in the case.

Soli Sorabji and Arvind P Datar have written/ edited a book titled 'Nani Palkhivala: A Courtroom Genius'. In this book they have given a reason for non-appearance of Palkhivala in the Habeas Corpus case. This is different than the one mentioned by Palkhivala.

At the end of this article (Appendix-I), I have annexed the reasons mentioned for non-appearance in the book 'Nani Palkhivala: A Courtroom Genius', my letter to Palkhivala, and his reply to me. The letter of Palkhivala is the scanned copy of the original. It is self explanatory.

‘The time has come’ The Walrus said

‘To talk of many things:

Of shoes and ships and sealing wax-

Of cabbages—and kings-

And why the sea is boiling hot-

And whether pigs have wings’

Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll

Article 21 of the Constitution, guaranteeing the right to life and liberty, now cannot be suspended; not even during emergency: 44th Constitutional Amendment Act, passed unanimously has ensured it. But it is instructive to look back on ADM Jabalpur Vs Shiv Kant Shukla AIR 1976 SC 1207 (the Habeas Corpus case) decided during internal emergency (1975-77) and Liversidge Vs Anderson (1941) 3 AllER 338 (the Liversidge case) that played an important role before the Supreme Court.

The writ of Habeas Corpus has been described as 'a key that unlocks the door to freedom' and as the case dealt with its maintainability in the light of complete suspension of right to move the court for enforcement of Articles 14, 19, 21 and 22 of the Constitution, it has come to be known as the Habeas Corpus Case.

The Shah Commission, in its authoritative account of the emergency, mentions, 'The one single item which had affected the people most, over the entire country was the manner in which the power under the amended [Maintenance of Internal Security Act] MISA was misused at various levels.'

MISA was, what National Security Act (NSA) is today—an Act for preventive detention. Its misuse to a large extent became possible because of the decision of the Supreme Court in the Habeas Corpus case.

Jayprakash Narayan spoke for the nation, when he said that the decision in the Habeas Corpus case 'has put out the last flickering candle of individual freedom. Mrs Gandhi's dictatorship both in its personalised and institutionalised forms is now almost complete' (Statement issued 15 May 1976, Narayan Papers, Third Instalment, Subject File 323, NMML).

Granuille Austin in his book 'Working a Democratic Constitution, A history of the Indian Experience' observes, 'The Habeas Corpus case captures the Emergency as nothing else: its authoritarian and geographical reach; its inefficiencies, its meanness and occasional magnanimity; its evocations of judicial philosophies and degrees of courage among judges and lawyers; its testing of officials' consciences and their willingness to submerge them in duty; its restraint compared with authoritarian regimes and periods of authoritarian rule in other countries.'

The Makhan-Singh Case

On an earlier occasion, emergency was declared during the Indo-China war. At that time—unlike during internal emergency— the right to move any court for the enforcement of Articles 14, 21 and 22 was suspended under Article 359 (See End Note-1) only for the persons detained under the Defence of India Rules (DIR), the Preventive detention law at that time. It was a partial suspension.

In Makhan Singh Vs State of Punjab AIR 1964 Supreme Court 381: (1964) 2 SCA 663: (1964) 1 CrLJ 269 (the Makhan-Singh case), the Supreme Court interpreted the partial suspension to mean that rights were suspended only for persons legally detained under DIR. So a person illegally detained, could maintain the Habeas Corpus petition.

During internal emergency, Articles 14, 19, 21 and 22 were suspended in their entirety—without any reference to any law. It was unlike the earlier occasion. And when this time, the detenus filed Habeas Corpus petitions, the Government raised preliminary objections that:

- Article 21 is the sole repository of liberty;

- It has been suspended in its totality; and

- The writ of Habeas Corpus was not maintainable.

The State also sought to distinguish the Makhan-Singh case on the different phraseology of the notification suspending the rights.

All the High Courts, where the objection was raised, decided against the Government. And on the question relating to maintainability of the Habeas Corpus petition, the matter was taken in an appeal to the Supreme Court. The court while entertaining the appeals stayed the further hearing of the Habeas Corpus petitions on merits before the High Courts.

Arguments―Supreme Court

The arguments in the Supreme Court in the Habeas Corpus case began on 14th December 1975, before a bench consisting of Chief Justice AN Ray, Justice HR Khanna, Justice MH Beg, Justice YV Chandrachud and Justice PN Bhagawati, the five senior most Judges of the Supreme court. It is interesting to note how this bench was formed.

On an earlier occasion, it was announced that another bench consisting of Chief Justice Ray, Justice Beg and three other Junior Judges would be formed. The lawyers in general felt that senior Judges should decide such an important question as was being done on every other similar occasion.

A delegation of Senior Lawyers, led by CK Daftary, met Chief Justice Ray in Chambers to change the bench. To a query from the Chief Justice, Daftary said that the case is an unprecedented one and in case if any precedent was required it had happened earlier at the time of Justice SR Dass. One is not sure if this was true or was Daftary's on the spot brilliance. But Chief Justice Ray was an admirer of Justice Das. He changed the bench to the one including the five senior most judges.

Justice KK Mathew was next to Justice Khanna in seniority. He was senior than Justice Beg, Justice Chandrachud and Justice Bhagwati. He was not taken in the bench as he was to retire shortly.

Every leading counsel in the country, except Palkhivala, appeared for the detenus. At that time, two different versions for Palkhivala’s non-appearance were doing the rounds. The first one—he refused to appear, as he thought nothing was working. The second one—he was to appear and sum up the arguments but was not informed. In response to my query, he clarified,

‘I was asked to appear in Habeas Corpus cases. I had a strong feeling that no purpose would have been served. Except for Justice HR Khanna, we had a bench of hopelessly weak judges who would have done anything to gain the favours of the then government.’My letter to Palkhivala and his response is appended at the end of the article as Appendix-1.

Despite what Palkhivala says, many felt, had he appeared, the result might have been different. Advocacy is reserved for juries; nonetheless it has a role with the judges as well. A few months ago, Chief Justice AN Ray had constituted a full bench of 13 judges to reconsider Keshvanand Bharti case reported in AIR 1973 SC 1461. Palkhivala got this bench dissolved by the power of his advocacy. Well, what can anyone say on his non-appearance? Lawyers are masters of their conscience.

A day before the appeal was to be heard in the Supreme Court, the lawyers for detenus met at the residence of CK Daftary to chalk out the strategy. There was some talk whether Shanti Bhushan should lead the argument or VM Tarkunde. Ram Jethmalani clinched the issue by saying Shanti Bhushan would lead. Tarkunde had shown his reluctance to be in the delegation to meet the Chief Justice to change the bench.

In the conference, we also speculated about the judgement in the case. The meeting ended with Ram Jethmalani relating the latest joke in Bombay. He said, 'The Supreme Court of Timbaktoo has decided that a prostitute can be a virgin with retrospective effects.’

Shanti Bhushan added ‘And the Government had submitted, it does not change the basic structure’.

The mood in the conference was buoyant. After all every High Court had decided in our favour as far as the maintainability was concerned. The question was difficult but there was no way that the Supreme Court could decide against us.

The next day was the cold day of 15th December 1975. Niren De, the then Attorney General, began his arguments in the same fashion as the Government of those days was behaving―bullying the court. I do not mean any disrespect as his voice is hushed at present but he did create terror. There was so much terror that none of the judges asked any uncomfortable questions.

The second day Justice Khanna was to ask the first one, ‘Life is also mentioned in Article 21. Would Government arguments extend to it also?’

There was no halfway house. Without pause Niren De answered, ‘Even if life was taken away illegally, courts are helpless’. It is then that other (Justice Chandrachud, Justice Bhagawati) started asking uncomfortable ones. We were relieved.

By the time the advocates for the Union Government and State Governments finished their arguments, all effects of the first day had vanished. The mood of the court was cheerful and better.

A few of the judgements of Justice Krishna Iyer were cited. They were in favour of the detenues. However, they used some words that were not part of any dictionary. Justice Ray asked Shanti Bhusan if he could explain their meaning. Shanti Bhusan, with mischievous smile, said that he was educated in a Hindi Medium school and perhaps convent educated Attorney General could explain. Niren De was sitting in the court. He got up and with serious expression vehemently denied knowing their meaning. Many a time Justice Iyer’s contribution to the jurisprudence has been lost due to his language―but more of this at some other time. (Kindly see 'The Anxiety―To do Right―Remains'). We must remember that the important reason that Justice Holmes or Lord Denning could leave such an impact on the legal world is because the simplicity of their language.

PK Tripathi was member, Law Commission of India. During arguments, he moved an application for intervention in favour of the government. It was refused. He was asked to submit his arguments in writing. Lawyers in India are so used to oral advocacy that no one gives any importance to the written briefs. This proved fatal; at least, as far as Justice Bhagawati was concerned.

Justice Bhagwati went on to pay high tributes to the novel submission of PK Tripathi. It is not clear if this novel submission was due to his jurisprudential genius or rather lack of it. But Justice Bhagwati cannot be blamed on this score. We all know that important cases are decided first and reasons are discovered afterwards. (Kindly see ‘Decisions Are From The Heart Rather Than the Head’ and ‘In The Matter Of Epimendes’).

The Supreme Court reserved the judgement in the case after being argued for more than two months. However, the judgement was not pronounced even after a considerable lapse of time. The result was that illegal detentions were being continued. An application was filed on behalf of the detenus with a prayer that either the judgement be pronounced or stay order staying the further hearing of the Habeas Corpus petitions on merits be vacated.

It was expected that the government might lose the case by three is to two. So even if the judgements of every judge was not ready, the stay order could be vacated. It is only when this application was posted for hearing after a week that the doubts arose.

Judgements were read in the open court by the judges on 28th April 1976 (See End Note-2). All interest was lost after Justice Khanna read his. It was clear that he was the only one who had decided in favour of detenus. And this is how the Supreme Court gave the biggest blow to itself.

High Courts' Decisions

Seervai (Constitution of India: Appendix Part I The Judiciary of India) says that ‘the High Courts reached their finest hour during the emergency; that brave and courageous judgements were delivered ... the High Courts had kept the doors ajar which the Supreme Court barred and bolted’.

It is difficult to get hold of all cases of Habeas Corpus decided during emergency. Not all of them are reported. Some are reported in the journals that are difficult to get. A gist of the cases, reported in CrLJ and the other unreported decisions supplied by the counsel for the Union Government during arguments before the Supreme Court, show almost complete unanimity in the High Courts on the question of maintainability of the Habeas Corpus. Though some of the High Courts had dismissed the writ petitions on merits.

In the following cases, the court held that the habeas corpus was maintainable:

- The Allahabad High Court in a full bench of five judges Virendra Kumar Singh Chaudhary Vs DM Allahabad 1976 Nirnay Patrika 855,

- The Andhra Pradesh High Court in a full Bench of three judges P Venkataseshamma Vs State of Andhra Pradesh AIR 1976 AP 1;

- The Bombay High Court in KM Ghatate Vs Union of India AIR 1975 Bombay 324 and another unreported decision Criminal Application No 171 of 1975;

- The Delhi High Court in DS Kapoor Vs Union of India 1975 CrLJ. 1376 and two other unreported decisions Criminal Writ No. 121 of 1975 Mrs Bharati Nayyar Vs Union of India, decided on 15.3.75 and Criminal Writ No 149 of 1975 Mrs. Satya Sharma Vs Union of India decided on 31.10.1975;

- The Karnataka High Court in Unreported Writ Petition No. 3318 of 1975 Atal Bihari Vajpayeei Vs Union of India;

- The Kerala High Court in Fatima Beebi Vs MK Ravindranathan 1975 CrLJ 1164;

- The MP High Court in Subhashchandra Jain Vs DM Jabalpur 1975 CrLJ. 1174; Haji Ibrahim Vs State of MP 1975 CrLJ 1438, Shiv Kant Vs Addl Distt Magistrate Jabalpur 1975 CrLJ. 1809);

- The Rajasthan High Court in unreported Habeas Corpus petition no. 1606 of 1975 Nilapchand Kanungo Vs Union of India ; and

- The Punjab and Haryana High Court in Darshan Singh Vs State of Punjab 1975 CrLJ 1974.

- The Madras High Court in unreported Writ Petition no. 68755 of 1975 V Dalan Vs Union of India did not decide the question of maintainability of the Habeas Corpus petition but assumed that it was maintainable and decided it on merits.

It is relevant to point out that the State of Gujarat had always maintained that Habeas Corpus was maintainable. Its Advocate General had argued before the Supreme Court in favour of detenus on the question of maintainability, the only question argued before it. At the time Cong (I) was in the majority at the Centre but not in the State of Gujarat. A party in opposition at the centre ruled it.

It is rather strange that four judges of the Supreme Court chose to overrule such an overwhelming view expressed by the High Courts.

Lawyers

Among the lawyers who appeared in the Habeas Corpus case, Shanti Bhushan became the Law Minister during the Janata regime; Soli Sorabji the Additional Solicitor General, he subsequently became Attorney General under VP Singh and Atal Bihari Vajpayee government; Ram Jethmalani an MP and strangely SN Kacker, who had argued for the State of UP against the detenus, the Solicitor General of India (See End Note-4).

Rama Jois had appeared for the detenus in the Karnataka High Court and before Supreme Court in December 1975. He did not come back in January 1976. He was arrested under MISA. The reasons were not disclosed, but he was appearing on behalf of most important political leaders namely Atal Bihari Vajpayee and LK Advani detained in jail at that time.

Rama Jois was elevated as Judge of the Karnataka High Court, then Chief Justice of Punjab & Haryana High Court. Unfortunately he resigned. He thought he was unfairly dealt with: he should have been elevated to the Supreme Court instead of his junior. He was later appointed as Governor of Jharkhand and Bihar during NDA-1. He was also elected as Rajya Sabha MP in 2008, as a BJP candidate.

High Court Judges

Among the other Judges, who dealt with the Habeas Corpus cases at the High Court level, five of them, Justice Kailasam, Justice Chinnappa Reddy, Justice AP Sen, Justice V Balakrishna Eradi and Justice KN Singh (in that order) made it to the Supreme Court.

Justice Sen, Justice Eradi and Justice Singh had held against the Government. Justice Kailasam did not expressly decide this question but had dismissed the petitions on merits. Justice Singh, with lady luck in his favour, retired as Chief Justice of India. He was appointed Chairman of the Law Commission after retirement.

Surprisingly Justice Chinappa Reddy, of National Anthem case fame, Bijoe Emmanuel Vs State Of Kerala; AIR 1987 SC 748, had held that habeas corpus was not maintainable. This was a case other than the full Bench that had held that the Habeas Corpus was maintainable. He had decided in favour of the Government. But in all fairness, it must be said that his judgement was of one paragraph only: it appears that the question was not properly argued before him.

Chief Justice KB Asthana of the Allahabad High Court wrote his judgement in Hindi. It was for common man to read. It was full of rhetoric and reminded Lord Atkin’s dissent in Liversidge Vs Anderson 1941 (2) All ER 330 (the Liversidge case). After his retirement, he became member of Rajya Sabha.

Justice RN Agarwal of the Delhi High Court had also decided against the government in favour of maintainability of the habeas corpus petition. He was Additional Judge at that time. He had to pay the price for his judgement against the Government. He was not confirmed despite recommendations of the Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court, Chief Justice of India and the Law Ministry.

Seervai in his book Constitution of India Appendix Part I 'The Judiciary of India' observes; ‘Sixteen other High Court judges paid the price of such judgements by forced transfers. A threat of forced transfers was kept hanging over 40 other judges but failed to deflect them from their duty.’

In most of the High Courts, the question about maintainability of the petition was decided as a preliminary question. The Government had taken the matter to the Supreme Court in appeal against the decision on the preliminary point.

A few of the High Courts decided the question of maintainability against the Government but dismissed the case on merits. But the Delhi High Court not only held the Habeas Corpus to be maintainable but also allowed the same.

Supreme Court Decision

The majority in the Supreme Court in the Habeas-corpus case heavily relied upon the Liversidge case. The point involved in the Liversidge case was whether Regulation 18-B be given subjective or objective interpretation. It had nothing to do with the maintainability of the Habeas Corpus during Emergency or Articles 21 and 359. There was no need to refer to this case. Apart from this, it was no longer a good law at that time in England. A critique of this case appears as the next article of this chapter.

The Liversidge case was not quoted in most of the judgements of the High Courts. It was referred in the Delhi High Court judgement but the court rightly held that the Liversidge case was no longer a good law.

The majority judgement of the full bench of the Allahabad High court does not refer to the Liversidge case. The minority judgement refers to it but ignores the cases overruling it and plethora criticism of the decision in the journals.

It is also strange that majority decisions of the Supreme Court in the Habeas Corpus case neither referred to the opinion of jurists of England, nor the subsequent decisions in England overruling the Liversidge case. No one can say that they were not cited. They were referred to in the judgement of the Delhi High Court against which appeal was filed in the Supreme Court.

Nakkuda Ali’s case (1951 AC 66) was decided within 10 years of the Liversidge case. In this case, Lord Radcliff killed the majority view of the Liversidge case. It is more than 10 years since the Habeas Corpus case has been decided. We have tacitly accepted our shame but have yet to openly admit the mistake. It is after 41 years, in 1977, that we accepted it in Puttaswamy case. Nariman in his book 'The State of the Nation' comments (Page 128)

'Guided by the majority opinion in a decision of England's House of Lords in Liversidge (1942) - a wartime decision, which in England itself had been long since discredited – Chief Justice A.N. Ray (who delivered the majority judgement) went on to say:'Liberty is itself the gift of the law and may by the law be forfeited or abridged.17'However, Justice HR Khanna (the senior most Judge on the on the bench next to Chief Justice A.N. Ray) dissented. …The majority view of the Supreme Court (4:1) in ADM Jabalpur (1976) [the Habeas Corpus case] was the low watermark in Indian human rights jurisprudence.'

During internal emergency, Lord Denning had come to India to deliver VV Chitaley Memorial lectures. He delivered three at Bombay (on 1-1-1976), Nagpur (on 3-1-1976) and Delhi (on 5-1-1976). The third one was entitled 'Let Justice Be Done'. It was during the arguments in the Habeas Corpus case. All judges, including the members of the bench hearing Habeas Corpus case, were present. The theme of the talk was, how judges in England maintained rule of law—even at the displeasure of the executive. It was an inspiring lecture and appeared as if, he purposely chose the topic for Delhi talk. He seemed to be admonishing them about the case. But, alas, it fell on deaf ears.

Supreme Court Judges

Among the judges who decided the case in the Supreme Court, Chief Justice Ray retired into oblivion.

Justice Beg superseded Justice HR Khanna and became the Chief Justice of India. He went on to clarify 'In re Shyam Lal' AIR 1978 S.C.489, a case decided after emergency that:

- It was never held that Habeas Corpus was not maintainable;

- Justice Khanna’s view was the unanimous view of the court; and

- The operative portion of the order in the Habeas Corpus the case was misleading.

In the Keshvanand Bharti case (AIR 1973 SC 146), the Supreme Court held that fundamental features of the Constitution cannot be amended; its basic structure cannot be changed. Some judges had refused to sign the conclusions in the Keshavanand Bharti case, as according to them they were not correct. But in the Habeas Corpus case the operative portion was signed by all judges including Justice Beg.

Maybe we should switch over to our mother tongue. English after all is an alien language. Many do not comprehend it well.

Seervai (Constitution Law chapter ‘The Judiciary and the Emergency’) also says that the operative portion of the order of the Supreme Court is not in accordance with the body of the judgements. But the damage had been done. In conformity with the operative portion of the Habeas Corpus case, the High Courts (End Note-5) dismissed the petitions as not maintainable. Their superior had crippled them.

It was clear during arguments that Justice Ray and Justice Beg would decide in favour of the Government. But what surprised everyone was the judgement of Justice Chandrachud and Justice Bhagwati. No one had expected that.

Subsequently, Justice Chandrachud gave a public apology. And we all know that soon thereafter Justice Bhagwati wrote that famous letter to Indira Gandhi (End Note-6).

Granuille Austin in his book 'Working a Democratic Constitution, A history of the Indian Experience' rightly sums up,

'In cynics' eyes, three of the bench saw a relationship between their rulings and their prospects on the Court. Justices Beg, Chandrachud, and Bhagwati were aware that in the normal process of seniority they would become Chief Justice one day, held for the government to assure that this took place.

...

It is very doubtful if the justices, metaphorically speaking, would have been hanged separately if they had hung together. Ruling against the government would have given them, and the Supreme Court as an institution, stature in public eyes such as to give even Mrs. Gandhi pause.'

After the emergency, the Janta Government, despite objections from many, appointed Justice Chandrachud as the Chief Justice of India. Loknayak Jai Prakash Narayan was hospitalised in Bombay. Shanti Bhushan, the then law minister, went all the way to Bombay to convince him that it was a right move. This may be at the instance of Morara ji Desai, the then prime minister of the country, who wanted Justice Chndrachud to be so appointed (See End Note-7). Many thought that Palkhivala might be directly appointed as the Chief Justice of India. However, he was appointed as the Indian Ambassador to USA.

Justice Chandrachud and Justice Bhagwati were brilliant judges but their career, their brilliance is eclipsed by their judgement in the Habeas Corpus case: they failed the judiciary, the nation, the people of India in the crucial time; they are not to be emulated but are rather to be shunned.

Justice Khanna became world famous overnight. The New York Times remarked, ‘surely a statue would be erected to him in an Indian city’.

Justice Michael Kirby retired as a Judge of the High Court of Australia. I had met him at National Judicial Academy at Bhopal. He sent me an e-mail. Its full text is appended as Appendix-II to this article. In the e-mail, he says,

'I met Justice Khanna in Australia soon after this celebrated case. About five years ago, I called on him in Delhi and (to his embarrassment) bent down and kissed his feet. He is, as you say, an example to all judges of the essence of what is to be entrusted with the judicial seat.'

It is debatable whether Justice Khanna had the brilliance of Justice Chandrachud or Justice Bhagawati; but one thing is sure, he had better understanding of human nature. He understood it well that Hitler had come to power by legal means, by votes of ballots.

Justice Khanna, by his single dissent in the Habeas Corpus case, has become most famous Judge to have ever walked on the Indian soil. But he paid the price of his dissent. This is summed up by Fali S. Nariman in his book 'The State of the Nation'. He says,

'A.N. Ray on his retirement as Chief Justice on India on 28 January 1977 did not recommend the name of Khanna only because of the latter's judgement delivered during the internal Emergency – in ADM Jabalpur vs Shivkant Shukla (1976) – where he alone amongst five justices on the bench refused to countenance the facile view that 'liberty was itself the gift of the law' (Ray's words) and hence could be taken away by law! Before he retired at age 65, Ray had recommended that Justice M.H. Beg (judge number 3 in the hierarchy) be appointed as Chief Justice – a controversial appointment; the event becoming known (unpopularly) as the 'Second Supersession'.

Nariman compares the Habeas corpus case with the decision of the US Supreme Court in Dred Scott {60 US, 393, 404-406, 419-420 (1857)} where Chief Justice Roger Taney speaking for a majority held that a 'Negro' (a term now considered offensive), whose ancestors were imported into the US and sold as slaves, could never become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States: He could never be a 'citizen' of the United States of America. He further adds,

'However, there is one thing in common between the decisions in Dred Scott (1857) and in ADM Jabalpur (1976) given more than a hundred years apart. In each of them, there were powerful dissents: testimony to the independent thinking of individual justices in the highest courts of two of the largest democracies in the world!'

The Liversidge case was decided in the middle of the twentieth century. Except for Lord Atkin, no one remembers, who were the other judges who decide the case (the other judges were Viscount Maugham, Lord Macmillan, Lord Wright & Lord Romer). Sufficient water under the bridge is yet to flow in India. Nevertheless, the judges, in majority of the Habeas Corpus case, are remembered only for their shameful judgement in the case, despite the fact, that they did write some good judgements.

No one approves of the emergency or the judgement in the Habeas corpus case. But then, though disapproved by the Constitutional (44th Amendment) Act, it stood for 41 years till it was overruled in the Puttaswamy case. One is not sure, if judicial activism by the Supreme Court, is an effort to redeem itself; maybe a psychiatrist can tell.

|

| My father, VKS Chaudhary speaking at the function of the Bar Association to honour him |

IT LIES IN THE HEART

Independent India's Darkest Period।। Supreme Court's Shame।। More Executive Minded Than The Executive।।

End Note-1: There is no such provision in the American Constitution. During internal emergency, a fictional novel 'The R Document' by Irving Wallace became very popular. It dealt with a plot about proposed similar amendment in the US Constitution.

End Note-2: This tradition of reading entire judgements in the Supreme Court has now been rightly done away with. It was never followed in the High Courts; at-least in recent times.

End Note-3: At the time Cong (I) was in the majority at the Centre but not in the State of Gujrat. A party in opposition at the centre ruled it.

End Note-4: He was the Advocate General when the matter was argued before the High Court in the 1st round and the Supreme Court. He, however, resigned when the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh was changed. He later on became Attorney General of India for a short time and then Law Minister under Charan Singh.

After my retirement as Chief Justice of the Chhattisgarh High Court, I started practising in the Supreme Court. One day, I was sitting in the Supreme Court Bar Association, there was discussion on SN Kackkar. I was surprised to hear that he opposed emergency. When I told him them that he supported emergency and had argued the case in favour of emergency, no would believe me. In order to support my point, I asked the librarian that to bring me reports where Habeas Corpus case is reported so that I could show them that the names of the lawyers and for whom they had appeared but found that in all of them only those pages were missing.

End Note-5: After the decision of the Supreme court this question was argued at length before a bench of Justice KN Singh and Justice BN Sapru in the Allahabad High Court It was opposed by Raja Ram Agarwal, who had then become Advocate General of UP in place of SN Kacker. The Court understood it well but expressed its helplessness in view of the Supreme Court decision. This is similar to another incident.

A petition was referred to a full bench of three judges with three questions. It had to be dismissed if even one question was decided against the petitioner. The first Judge decided 1st question against the petitioner; questions no 2 & 3 in favour of the petitioner and dismissed the petition. The second Judge decided the 2nd question against the petitioner; questions no.1 & 3 in his favour and dismissed the petition. The third judge decided 3rd question against the petitioner and questions no. 1 & 2 in his favour and dismissed the petition. The operative portion of all the three judgements is to dismiss the petition. But if the bodies of the judgements are seen then two out of three have answered each question in favour of the petitioner. The petition should be allowed.

End Note-6: Indira Gandhi won the election in 1980 after Janta Government fell. It is at that time Justice Bhagwati wrote a letter praising Mrs. Gandhi. One wishes he had not written that letter.

End Note-7: SS Khanduja was AOR for my father in the Habeas Corpus case. After Puttuswami case, where Habeas Corpus case was overruled, we were talking about those time and he told me that a delegation of Jansangh (erstwhile BJP) lawyers had gone to meet Morarji Desai not to appoint Justice Chandrachud as chief justice of India. He was part of that delegation. Morarar ji Desai told them they should not worry as Justice Chandrachud did what Indira Gandhi told him to do as she was in power; now we (Janta Party) are in power and he will do as we will ask him to do.

APPENDIX-I

Non-appearance of Nani Palkhivala

Soli Sorabjee and Arvind P Datar have written a book 'NANI PALKHIVALA The COURTROOM GENIUS' published by Lexis Nexis Butterworths Wadhwa. In the book there is a chapter 'The Habeas Corpus Case: Palkhivala's Critical Absence'. In this they explained the reason for his non-appearance as follows:'Sorabjee and other advocates had requested Palkhivala to come to appear in the Court. Palkhivala's response was that there was no way that the Court would allow the appeals of the Government especially after seven High Courts delivered well-reasoned decisions in favour of the citizen. His view was that it was an open and shut case and nothing would be gained by his appearing before the Supreme Court. Palkhivala felt that Chief Justice Ray and Justice Beg would possibly hold in favour of the Government. He was completely confident about Justice Chandrachud and Justice Bhagwati holding in favour of the citizen. Indeed, ironically, he felt that it was Justice Khanna who could be “the dark horse” but could be persuaded to dismiss the appeal and uphold the right to liberty'

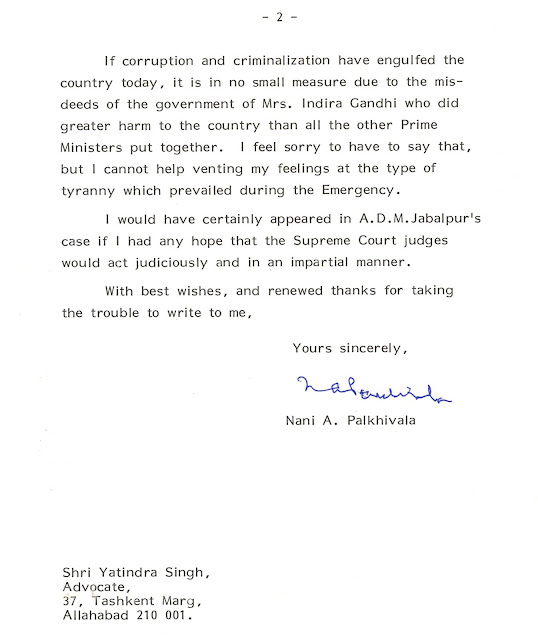

Perhaps, the aforesaid reason is not correct. Before writing the article 'The Habeas Corpus Case' I had written a letter to Mr. Palkhivala requesting him to get the correct version for his non-appearance. My letter dated 22.12.96 and Palkhivala's reply dated 13.1.97 are as follows:

Dear Mr. Palkhivala, Date: 22.12.1996

Thank you for your letter dated 19th Nov, 1996. I am interested in writing and have written few articles. I want some information about an article relating to the Habeas Corpus case that is ADM Jabalpur Vs Shiv Kant Shukla, AIR 1976 SC 1207. My father Mr. VKS Chaudhary is a Senior Advocate. He was detained during emergency and we had filed Habeas Corpus. As you know we lost the case before the Supreme Court. You did not appear in these cases. Many of us believe that we might have won the case had you appeared in the matter. What was the reason for your nonappearance? There are two versions which I have heard. Which one is correct or was there any other reason?

- The first one, 'Mr. Palkhivala had agreed to appear before the Supreme Court for the detenus and was to be informed. But unfortunately under some confusion he was not informed and as such could not appear'.

- The second one, 'Mr. Palkhivala was contacted (probably by Nana Ji Deshmukh) but he said that he works when laws and Constitution are followed. Since nothing is being done which is legal, he expressed his inability.'

I am also enclosing copies of two of my latest articles. The first one 'In the matter of Epimendes' is an inter disciplinary study. It discusses impacts of paradoxes in the field of Mathematics, Literature, Philosophy and on jurisprudence. It examines the connection between one of the oldest and the most talked about paradox namely 'liar's or Epimendes' paradox' and decision making process.

The second article, 'In the matter of a judge' traces history of law in respect of liability of judges while acting judicially.

Thanking you,

Yours faithfully,

(YATINDRA SINGH), 37, Tashkent Marg, Allahabad-210001.

Reply of Mr. Palkhivala dated 13.1.97

This letter indicates that the reasons for non-appearance of Palkhivala were different from those mentioned in the book 'COURTROOM GENIUS'.

APPENDIX-II

Email of Justice Michael Kirby, Judge, High Court of Australia

Dear Yati,

It was, a great pleasure to meet you in Bhopal. Your splendid book A Lawyer's World was my companion on the long journey home to Australia. Thank you for giving it to me.

I was specially moved by your essay on dissent and in particular the dissent of Justice Khanna in the Supreme Court in the habeas corpus application during the Emergency.

I met Justice Khanna in Australia soon after this celebrated case. About five years ago, I called on him in Delhi and (to his embarrassment) bent down and kissed his feet. He is, as you say, an example to all judges of the essence of what is to be entrusted with the judicial seat. Thank you for writing in such a vivid way about him.

Thank you also for comments on issues of sexuality. I liked the way that you weaved science and reality into your legal thinking. I hope that we will meet again and that, meantime, your career will continue to flourish and your life be full of happiness.

Sincerely,

Michael Kirby

#Liberty #HabeasCorpusCase

No comments:

Post a Comment